MAPS 2 - SOUND IN THEATRE, CINEMA AND MULTIMEDIA

2023-12-09

These writings, commissioned by UNAA x ArtNexus Program, will not merely shed light on the artistic production and distribution; they aim to critically analyse and document the prevailing conditions and methodologies that artists navigate. By doing this, they not only bolster the advocacy facet of the ArtNexus initiative but also weave art back into the fabric of everyday conversations, stimulating economic growth within the sector.

____________________________________________

Sound is a fundamental element in the realms of theater, cinema, and multimedia. With the advent of recording and reproduction technologies, sound has gained an extraordinary expressive power, markedly distinct from its capabilities prior to these inventions. These technologies enabled sound to "be detached" from its original source and achieve a newfound independence. From that moment on, recorded sound could be manipulated – played back, sped up, or slowed down, provided there are devices to reproduce them. Moreover, these sounds can be artistically merged in various creative forms. This is exemplified by the emergence of genres such as musique concrète, electroacoustic music, and electronic music, all of which testify the innovative experimentation made possible by these technological developments.

Another fascinating aspect of this "liberated" sound is related to how it could be paired with images, movements, and objects that, as Walter Murch observes, may be completely unrelated to the original context or object that produced it

These dynamics have also spurred corresponding scholarly reflections. Notably significant in this context is the work of Michel Chion, "L'Audio-Vision. Son et image au cinéma" (Audiovision: Sound and Image in Cinema), published for the first time in 1990. This book delves into the symbiotic relationship between sound and image, exploring how the senses influence and transform each other, and examining the role this interplay plays in shaping our auditory and visual perceptions.

Chion's perspective can serve as a form of awareness beyond cinema, regarding the role of the soundscape within theatrical, cinematographic, and multimedia works, encouraging us to listen and understand how it is created, the role technology plays in this creation, and how this soundscape interacts with other senses

Albania, due to its dictatorial and isolating context, lagged behind in keeping up with the developments of sound technologies, also because the potential high costs of technological investments for music recordings or film production could strain the Albanian state economy. The technology used remained at modest levels. Sound recordings were managed even in stereo mode, yet the playback often remained mono, significantly affecting the listening experience. In Albanian cinema, the entirety of sounds - dialogue, music, effects, noise - was edited in the studio. This approach was not a directorial choice but rather a necessity due to the impossibility of doing it differently. For those who have greater aural amenability, this meant a general uniformity of the film sound, problems with synchronization, and a certain artificiality compared to the more "realistic" reflection of on-set sounds. The latter were recorded merely for orientation. (On the other hand, lack of technology contributed to the scarcity of sound effects and noises).

From this perspective, the work of sound engineers or editors in Albania remained constrained and, to some extent, "spartan." They had to find solutions that could have been much more easily achieved with up-to-date technology. Nevertheless, this did not hinder special collaborations, highlighting the importance of sound engineers like Spiro Konduri, Asim Raxhimi, and others in the film industry. In the realm of theater, the limitations regarding sound and technology were even more pronounced, however despite these constraints, there was no shortage of innovative solutions in the intelligent use of sound and music, as exemplified in the works of Pirro Mani or Mihal Luarasi.

This topic is extensive, particularly in considering the agency of these professionals; how they managed to work within a centralized and restrictive environment. Overall, however, it demonstrates that, unlike internationally, Albania's sound technology failed to realize its full potential. Similarly, it would be incomplete trying to understand the complex post-communist landscape without acknowledging a kind of auditory impoverishment, as described by Florian Çanga

Overall, however, it demonstrates that, unlike internationally, Albania's sound technology failed to realize its full potential. Similarly, it would be incomplete trying to understand the complex post-communist landscape without acknowledging a kind of auditory impoverishment, as described by Florian Çanga. This auditory deficit, along with economic and social poverty, was a legacy of the past

As a result, in the past 30 years, development in this field has largely been driven by individuals passionate about working and experimenting in sound technology, in the absence of a stable environment willing to support their ideas and ventures. This situation has placed them in constant, often intense, confrontation with several challenges, including: the socio-political climate, technological hurdles, the shortsightedness and insensitivity of colleagues or institutions not always receptive, the lack of funding, and the hurdles posed by a non-existent market devoid of any clear rules. Consequently, these individuals have made personal and professional choices that, from a broader perspective, underscore the fragility of their initiatives within an artistic reality still struggling to confront not only the external artistic world but also its own challenges.

Consequently, these individuals have made personal and professional choices that, from a broader perspective, underscore the fragility of their initiatives within an artistic reality still struggling to confront not only the external artistic world but also its own challenges.

The cases I have chosen to focus on appear as isolated creative episodes. Yet, they still provoke thoughtful consideration of sound. These works, significant in their own right, have not been adequately documented, particularly when it comes to theater. To revisit them, I worked closely with the authors, who also provided access to their works. This was complemented with interviews and conversations (sometimes virtual), fostering a kind of introspective reflection from each artist about their works. Temporal distance played a great role for that.

Firstly, I'd like to focus on the works of Gentian Shkurti. In 1997, during his second year of university, Shkurti began exploring video art as a distinct genre for experimentation and self-expression

In this work, Shkurti’s aesthetic statement is built up by first focusing on the image, to which he later adds music. At this point, we can draw a parallel with the music video Shkurti produces two years later for Bojken Lako's song "Merre [stresin] lehtë / [Take it easy]". Here, Shkurti reverses his approach by crafting the visual narrative from the music. In this instance, we encounter a stream of seemingly simpler images that visually comment on the song's content

Collaborations similar to the one between Lako and Shkurti also distinguish the works of director Ermela Teli and composer Mardit Lleshi. For Teli, sound is a character in itself

Architecture of Sadness (2012) explores different sound features. The film is structured around three episodes, linked by an emotional thread and the need to narrate certain situations audio visually. It begins with a non-feminist reinterpretation of the legend of Rozafat's wall, followed by episodes from the dictatorial period and the transition. In the first two chapters, the film primarily uses sound effects and noises to create a realistic "mirror" of the diegetic sounds within the shot scenes (such as footsteps on grass, whispered words, the clinking of stones, and notably the sound of a ping-pong ball, which transitions from diegetic to extra-diegetic, becoming a sonic “theme”). Thus, this transition from the “musique concrete” sound state in the first two chapters to the third chapter's use of musical themes sounds surprising and contradictory: it begins with a cello accompanied by an electronic background of effects and rhythms, culminating in an improvised solo. In this final part, the camera centers on the performer, Mardit Lleshi himself, playing "live" on a neutral stage (the only backdrop is a wall where his shadow is cast), captured in black and white photography with emphasized light and shadow contrasts, until the scene fades to darkness, paving the way for the closing credits.

The sound work is a product of the director's collaboration with French sound engineer Nicolas Verhaeghe. On the other hand, Mardit Lleshi develops his unique musical language, which seamlessly blends his roles as both instrumentalist and composer, while incorporating either the acoustic or the electronic dimensions of music and melding improvisation with music composition. Finally, source music is intertwined with studio-produced audio edited for accompanying the images. Lleshi's distinctive musical language complements the film's visuals in a notably poignant manner, something that is further enhanced by the film's unconventional montage.

Theater might seem to offer fewer possibilities for sound compared to film and multimedia. However, technological advancements have demonstrated the opposite. In Albania, only a handful of directors have fully explored this potential. Notable among them are Enton Kacaj and Ergys Lubonja for their work on Ionesco's Chairs (October 2005)

Among all the works mentioned, "Freedom in Bremen" by Sesilia Plasari stands out as an artistically profound conveyance of the significance of sound in relation to all other components. This emphasis on sound begins right from the initial table read and continues through to the final show

Sesilia Plasari’s significant message to the audience is not to be passive, like cattle heading to the slaughterhouse, as depicted in the show, but to cultivate an observational instinct, to be attentive to their actions in relation to life and others

The examples discussed illustrate that working with sound can be even more complex than with visual imagery, and that technology and creative aesthetics are intricately intertwined. Consequently, one of the primary areas warranting critical attention is the professional profile of individuals who specialize in sound. Until the early 1990s, these roles were mainly limited to sound engineers and sound operators, whose skills were particularly valued among professionals directly involved in sound work. Today, however, there is a much broader variety of roles in this field. These include on-set sound recordists, sound engineers (also known as foley artists, who focus on effects), sound designers, and composers. Each of these roles contributes to the rich tapestry of auditory experiences in various media. This constitutes a distinct team, which often functions within a company or a network overseeing each stage of a film's production. In the absence of such a team, an alternative for those with financial resources is to collaborate with foreign studios. The productions lacking such a work on sound are often distinctly recognizable, at least based on my experiences at film festivals, for their sound quality and the presence of certain flaws, such as barely audible dialogue, overly heavy effects, or other perceptible details.

In Albania, specialized profiles in sound technology are scarce, and those who exist typically work as freelancers. Recognizing these challenges, pragmatic solutions are often adopted. Video artists like Gentian Shkurti choose not to invest in high-tech equipment in a financial environment that might limit his creative freedom. On the other hand, on-set recorders like Bardhyl Xhani or Endri Pine are cautious with technological and infrastructural expenses. This caution stems from the limited opportunities for this type of technology to justify the investment, as well as a lack of awareness among directors about the importance of sound.

Investing in sound quality also means investing in technology, which seems paradoxical given that current theater halls, such as Ar-Turbina, lack even the most basic acoustic parameters, and cinemas require updates with modern audio systems

Moreover, education should focus not just on professional training through schools or courses, but on fostering a more comprehensive education in active listening. This approach emphasizes the idea that sound, before being an object on its own, is primarily a whole culture.

Acknowledgment:

I extend my gratitude to those who shared their information and data, contributing to the realization of this essay: Elsa Demo, Spiro Konduri, Gentian Shkurti, Ermela Teli, Mardit Lleshi, Endri Pine, Enton Kacaj, Florian Çanga, Eno Milkani, Bardhyl Xhani, Renis Hyka, and Adriana Tolka.

Captions for the photographs in the gallery:

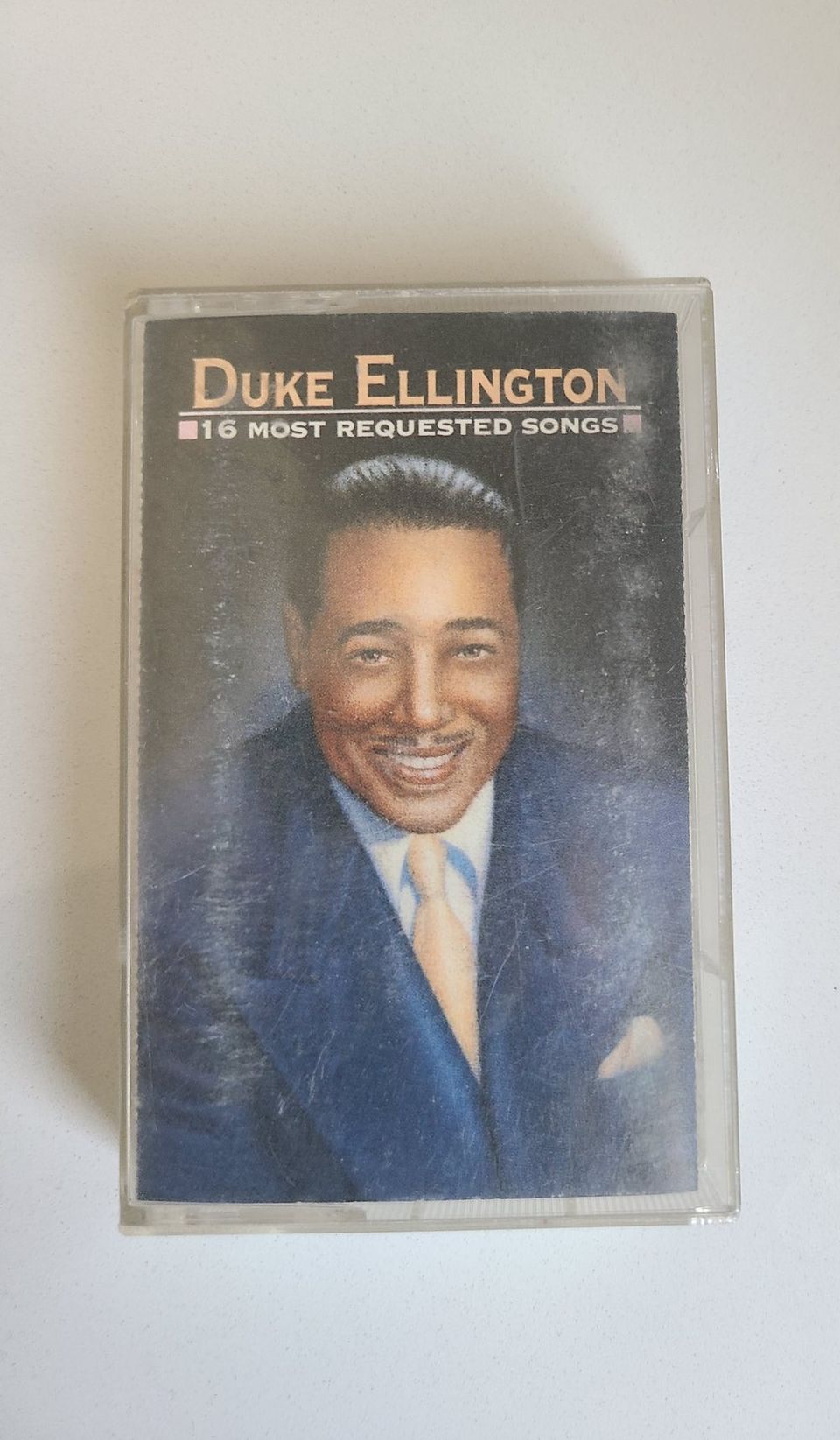

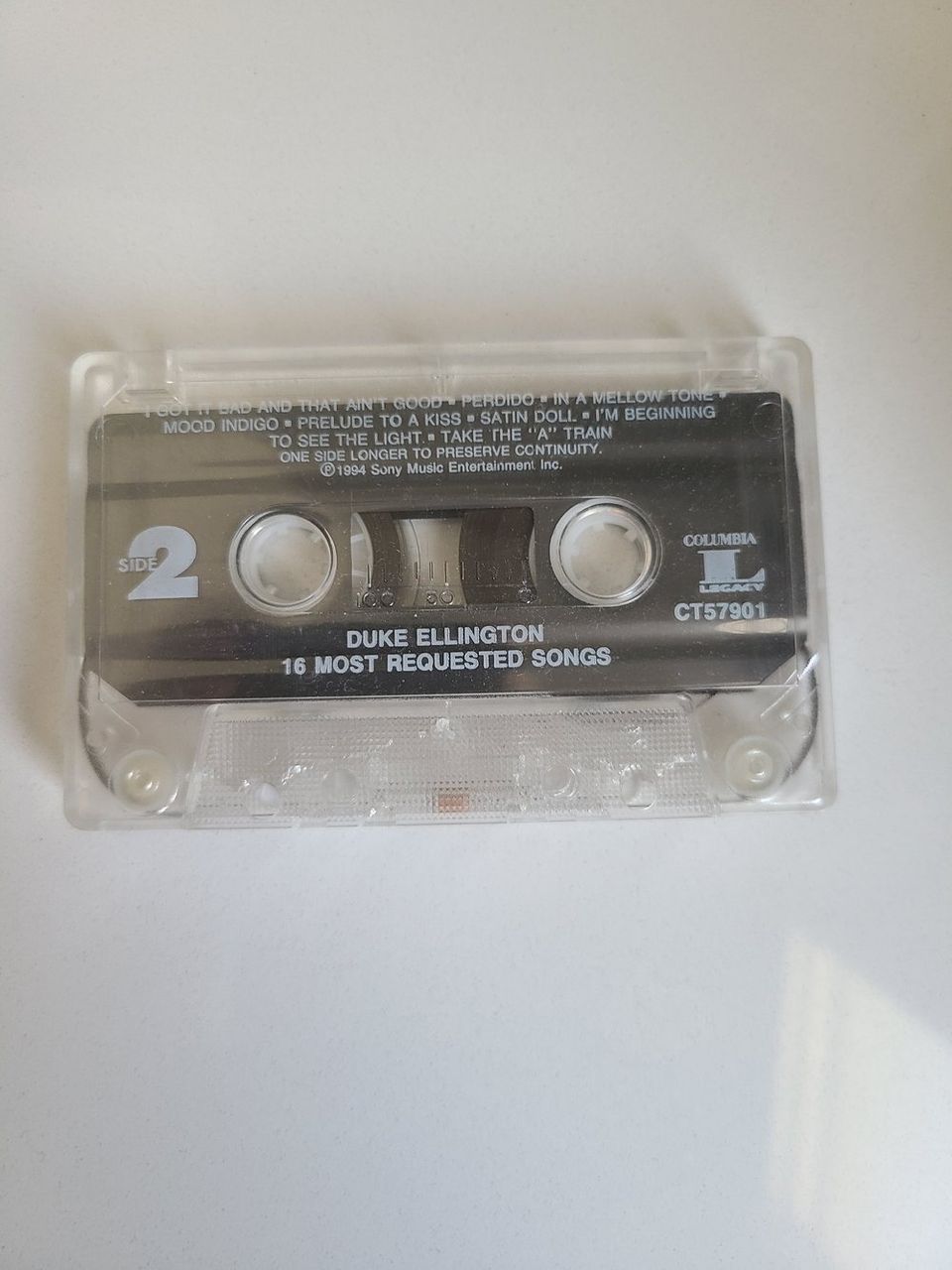

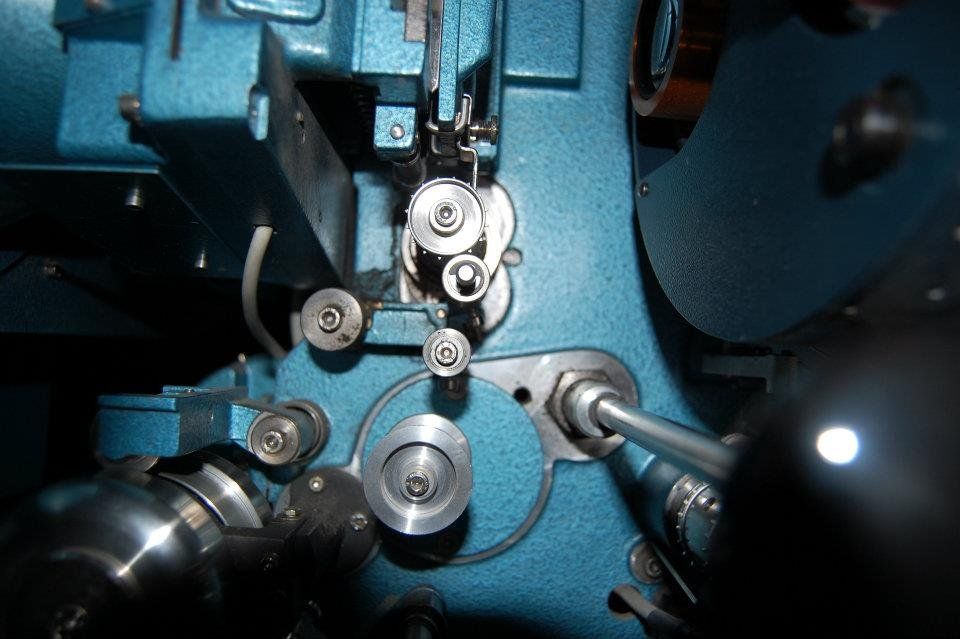

Photo 1 and 2: Duke Ellington's original audio tape used as sound for Alice in Wonderland by Gentian Shkurti. Photo by Gentian.

Photo 3: Image from the movie Homage directed by Ermela Teli (2010)

Photo 4: Image from the film Architecture of Sadness directed by Ermela Teli. (2012). In the photo: composer and cellist Mardit Lleshi while performing.

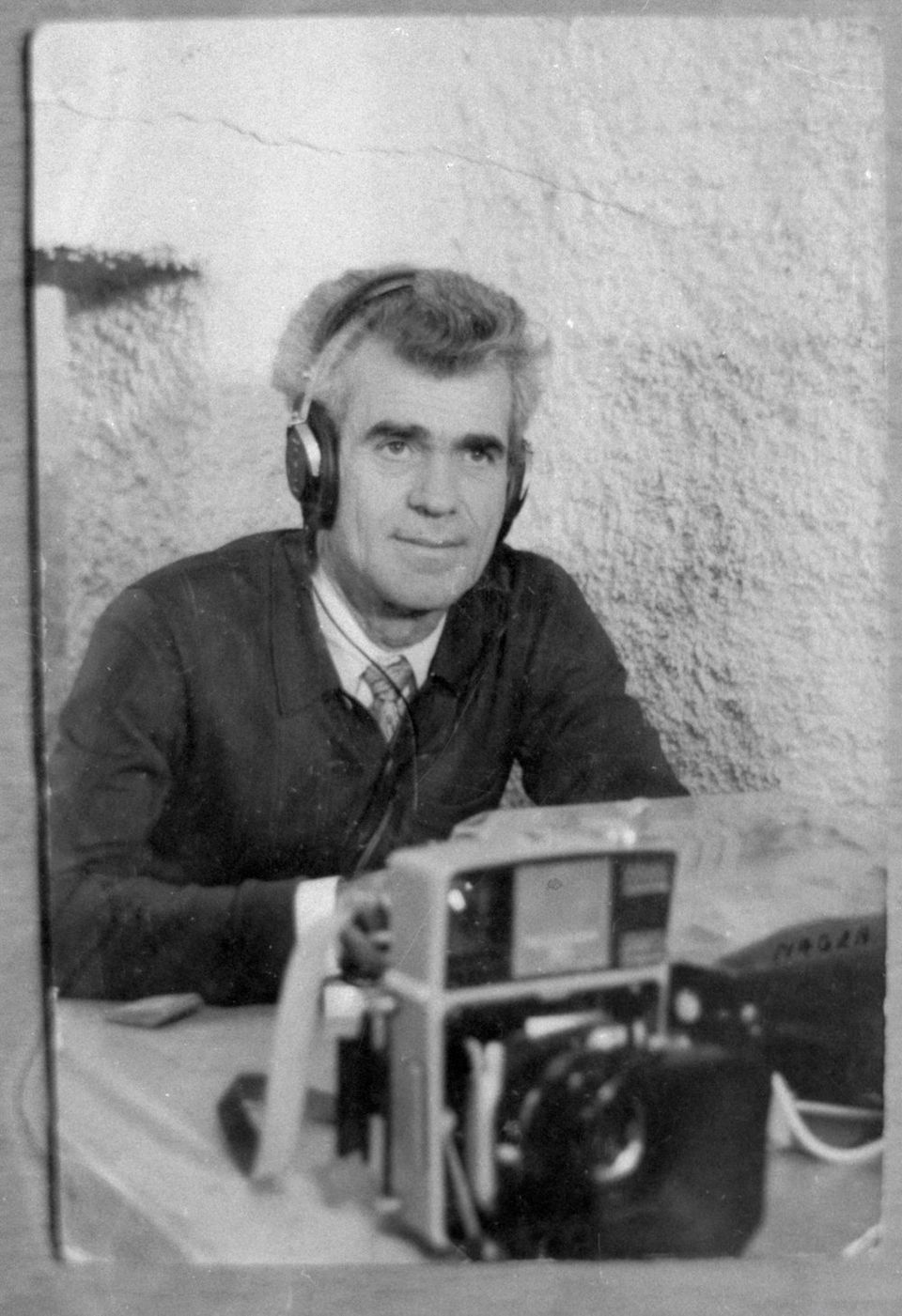

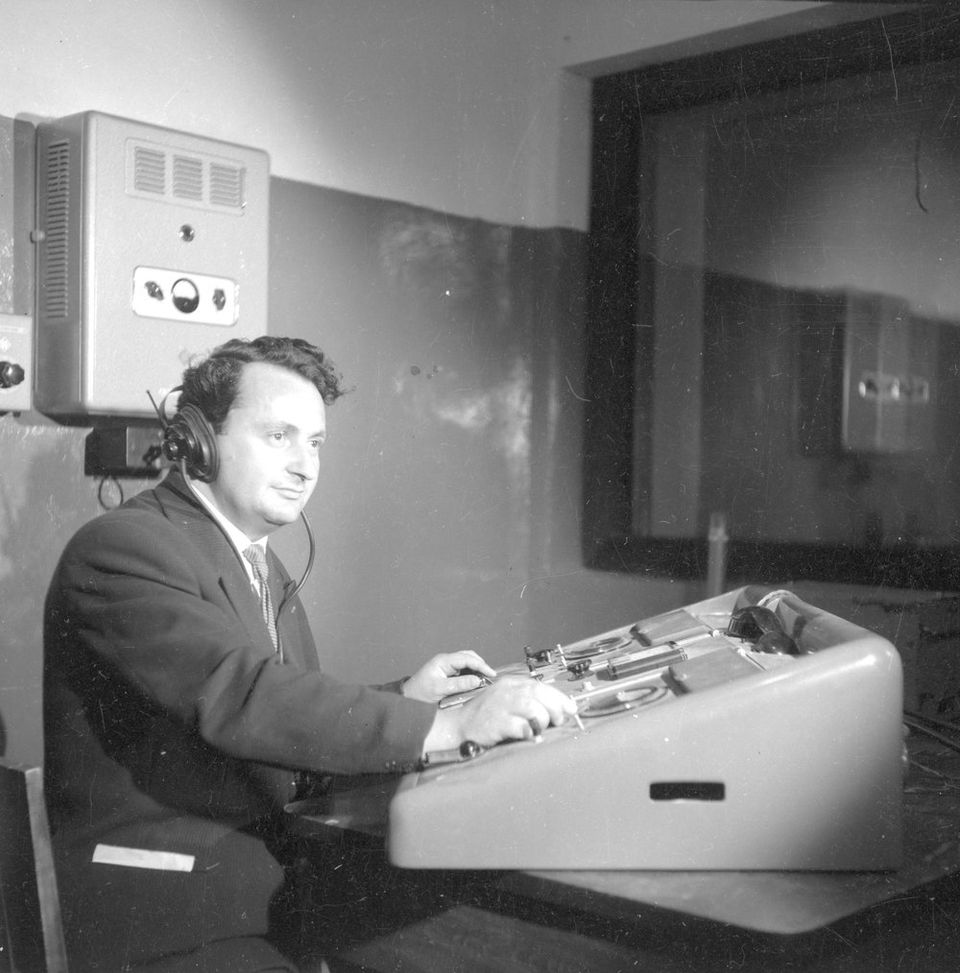

Photo 5: Asim Raxhimi, AQSHF

Photo 6: Spiro Konduri, AQSHF

Photo 7: Xhevat Behri, sound Operator, AQSHF

Photo 8: Photo by Florian Çanga

Photo 9: Photo by Florian Çanga

Photo 10: Photo by Florian Çanga

Photo 11: Endri Pine. My Lake shooting set. Directed by Gjergj Xhuvani (2018)

Photo 12: Endri Pine. My Lake shooting set. Directed by Gjergj Xhuvani (2018)

Photo 13: Ermela Teli. Audio recording day for Audio Installation Wall. (2014)

Photo 14: Film set for Wicked Game. Directed by Ermela Teli (2012)

Photo 15: Shooting set for Girl with Suitcase directed by Ermela Teli (2015)

Photo 16: Conversation with Mardit Lleshi, 11.07.2023

Photo 17: Classroom for the course on Video and Sound Design for Stage in Verona. Photo by Florian Çanga

Photo 18: Image from the drama Blackbird (2016). Photo by Florian Çanga

Photo 19: Poster of Bremen Freedom

Photo 20: Poster of Blackbird

About the author Mikaela Minga

Mikaela Minga is an ethno/musicologist at the Institute of Cultural Anthropology and Art Studies in Tirana. She's currently head of the Department of Folklore. Also, Minga is a guest lecturer at the University of Arts for the subjects: Music and film, Jazz and popular music. Her research field includes music of the 20th century (both traditional, popular and artistic). She has a specific focus on urban musical practices in Albania and the Mediterranean; studies on sound and sound archives; film music, as well as the dynamics of music in dictatorial regimes. She is the author of several monographs such as: Luciano Berio and Folk Song, 2008; Spanja Pipa e la canzone urbana di Korça, 2015 (with Nicola Scaldaferri as co-author), Sounds that tell, sounds that are told, 2020; the musical album Armenian songs from Drenova/Arumune songs from Drenova, 2018 (prepared in collaboration with Josif Minga) and a series of articles and essays.

Walter Murch. “Foreword”, XVI. In Michel Chion. Audio-vision. Sound on screen. Columbia University Press. 1994.

The concept of "soundscape"(sound landscape) was formulated by Canadian composer and researcher R. Murray Schafer in his book The Soundscape: The Tuning of the World and Our Sonic Environment, published in 1977.

Florian Çanga, personal conversation, September 1, 2023.

Florian Çanga, personal conversation, September 1, 2023.

Gentian Shkurti, personal conversation, 14 July 2023.

The details regarding the making of Alice in Wonderland are sourced from a personal conversation with Gentian Shkurti on July 14, 2023.

Bojken Lako, “Merre lehtë”. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZaHEtoxTQ1o. For insights into the creation of the video clip, I have also turned to interviews from the "Tie-In" exhibition on the history of the Albanian video clip, curated by Donika Çina, were consulted. This exhibition took place at the Boulevard Art Media Institute in Tirana, from November 26, 2021, to January 15, 2022.

Ermela Teli, personal conversation, 13 gusht 2023.

A news clip of the time is available for consultation at this link:

A video from the live performance is available at this link:

Some footage from the performance can be viewed here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wTj65w_mcLY

The conversation between the director and journalist Elsa Demo can be found here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=m-ibgK4RqW4

Enton Kacaj, virtual conversation, 16 korrik 2023.

Both Sesilia Plasari and Florian Çanga emphasized this particular detail of their work in the personal conversations I had with each of them.

Plasari's comment is taken from an interview with journalist Elsa Demon. See: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=m-ibgK4RqW4 , 7’00’’.

Plasari's comment is taken from an interview with journalist Elsa Demon. See: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=m-ibgK4RqW4 , 7’00’’.

For an account on the current state of cinemas, I would suggest the contribution of Elsa Demo in this series: A listless cinematic culture (and a brief trip with my niece) https://arca.al/en/articles/a-listless-cinematic-culture-and-a-brief-trip-with-my-niece/